The LungeIn January 2023, my family and I went on a vacation to Florida. While playing football with my little brother on the beach, I accidentally jammed my big toe into a tough patch of sand. At first, I didn't think much of it and kept playing. However, in the following weeks, I experienced persistent pain in my big toe when running and lunging. This condition is commonly known as 'Turf Toe,' but the most important thing is knowing how to treat it. Lunging, squatting, and hip-hinging are three of the strongest movement patterns for lifting things. Each of these movements requires different body mechanics. Since the big toe and ankle joints play a crucial role in providing stability during these exercises, I was experiencing pain while running and lunging. These movements require a significant amount of big toe extension, which I had lost due to the injury. Losing this seemingly small movement completely changed how I lunged. Although it may seem insignificant, I felt like I had lost one of the most efficient ways of lifting heavy things. To get out of pain, I had to gradually retrain my lunge. In the post below, I will review lunge mechanics and break down the movement into smaller, more digestible pieces. Lunge MechanicsThe lunge involves hip, knee, and ankle flexion as one foot steps forward, engaging the hip flexors, quadriceps, and glutes eccentrically. The rear leg extends, activating the hamstrings, while the core stabilizes the torso. The body descends until the front thigh is parallel to the ground, then reverses direction through hip, knee, and ankle extension, with the glutes, quadriceps, and calf muscles concentrically contracting. Throughout, the core maintains stability, and proper alignment is essential for joint integrity. The lunge enhances lower body strength, balance, and mobility, making it a fundamental exercise in fitness programs. Ankle and Big Toe MobilityBig toe mobility is essential for a lunge movement as it contributes to proper foot positioning and weight distribution. Adequate mobility in the big toe allows for efficient toe extension, which helps stabilize the foot and create a solid base of support during lunging. Improved mobility in the big toe facilitates better balance, proprioception, and force transmission through the foot, enhancing overall movement quality and performance. Limited big toe mobility can lead to compensations such as foot pronation or reduced push-off power, increasing the risk of instability, inefficiency, and injury during lunging exercises. Hip Flexor MobilityHip flexor mobility is essential for a lunge movement as it allows for proper hip extension and alignment. Adequate mobility in the hip flexors, particularly the iliopsoas, permits a deep lunge position with the front knee positioned directly over the ankle and the back knee close to the ground. Limited hip flexor mobility can lead to compensations, such as leaning the torso forward or arching the lower back, compromising form and stability. Improved hip flexor mobility enhances range of motion, promotes proper alignment, and reduces the risk of injury during lunging exercises. Adductor (Inner Thigh) MobilityHip adductor mobility is crucial for a lunge movement as it allows for proper alignment and stability of the lower body. Adequate mobility in the hip adductors permits the legs to move freely in the frontal plane, enabling a smooth and controlled lunge motion without restrictions or discomfort. Limited hip adductor mobility can result in compensations such as excessive knee valgus (inward collapse) or reduced range of motion, leading to poor form and increased risk of injury. Improved hip adductor mobility enhances the effectiveness of lunging exercises by promoting proper alignment, balance, and movement mechanics. World's Greatest StretchThe "World's Greatest Stretch" is a dynamic stretching exercise that targets multiple muscle groups and joints simultaneously, providing a comprehensive stretch for the entire body. It typically involves a series of movements that incorporate elements of hip flexor, hamstring, quadriceps, calf, chest, shoulder, and thoracic spine stretching, along with core activation and stability. While there's no single universally agreed-upon version of the "World's Greatest Stretch," a common sequence might involve a combination of the following movements: Single Limb StabilitySingle-leg stability in the lunge is crucial for maintaining balance and controlling movement throughout the exercise. As the body lowers into the lunge position, the supporting leg must stabilize against gravitational forces and resist lateral or rotational movements. This enhances proprioception and neuromuscular control, improving overall balance and coordination. Additionally, single-leg stability helps prevent compensatory movements and reduces the risk of injury by promoting proper alignment of the lower body joints. Strengthening single-leg stability in the lunge translates to improved functional movement patterns and enhanced athletic performance. Lunge Closing ThoughtsThe lunge movement offers numerous benefits, including improved lower body strength, muscle tone, and endurance. It targets multiple muscle groups, such as the quadriceps, hamstrings, glutes, and calves, while also engaging the core for stabilization. Lunges enhance balance, coordination, and proprioception, promoting functional movement patterns and reducing the risk of injury. Additionally, they can be modified to suit various fitness levels and goals, making them a versatile exercise for individuals of all abilities. Incorporating lunges into a workout routine can lead to greater overall fitness, mobility, and athletic performance.

5 Comments

I have to confess that I used to hate squatting. And I had a good reason for it! Whenever I used to squat, I experienced pain in the front of my right hip and my lower back. The movement felt awkward and disconnected. My ankles, hips, and lower back didn't move smoothly, so I couldn't properly engage my muscles. Over the past several years, I have gained a better understanding of how the body moves and functions. As a result, I have improved my mobility in the spine, hips, and ankles. I have also learned how to use my hip muscles to generate power. Now, when I squat, I can feel the work in my quadriceps, deep inner thigh muscles, and glutes. I no longer experience any joint pain and my lifts have gotten significantly stronger. Benefits of SquattingSquatting is a compound movement that engages multiple muscle groups simultaneously, making it one of the most beneficial exercises for the whole body. Primarily targeting the lower body muscles such as quadriceps, hamstrings, and glutes, squats also recruit core muscles for stabilization and balance. This comprehensive engagement not only strengthens the muscles involved but also enhances overall functional strength, facilitating everyday activities like walking, climbing stairs, and lifting objects with greater ease. Furthermore, squats promote joint health by increasing the strength and stability of the knee, hip, and ankle joints, potentially reducing the risk of injury and improving mobility. Beyond its impact on musculoskeletal health, squatting offers numerous additional benefits for the entire body. By stimulating the release of growth hormone and testosterone, squats promote muscle growth and fat loss, contributing to a leaner and more toned physique. Additionally, squatting engages the cardiovascular system, leading to increased heart rate and calorie expenditure, which can aid in weight management and improve cardiovascular health. Moreover, the functional nature of squats promotes better posture and body mechanics, translating into improved overall movement patterns and decreased likelihood of injury in daily activities and athletic endeavors. Mastering the SquatIn the videos that follow, I have broken down the squat movement into its various biomechanical components. Through these videos, I will guide you on how to effectively reassemble these components to create a powerful, functional, and pain-free movement. Hip Flexion: Getting Knees to Chest and Finding the Posterior ChainDuring the squat, hip flexion refers to the bending of the hips as the lifter lowers their body toward the ground. Hip flexion allows for proper depth and range of motion in the squat, enabling the lifter to achieve a full or parallel squat position. It also helps to engage the quadriceps, glutes, and core muscles more effectively, distributing the load across multiple muscle groups and joints. Upright Spine Position: Middle and Lower Back Extension MobilityExtension is vital in a squat as it helps maintain an upright torso position, reducing stress on the lower back and promoting alignment of the spine. During squatting, the lumbar spine undergoes both flexion and extension movements. Initially, it flexes slightly as the hips hinge backward, allowing the torso to tilt forward. As the lifter descends into the squat, the lumbar spine maintains a stable, neutral position, with slight extension to counterbalance the forward lean of the torso. It allows for better breathing mechanics, enhances stability, and enables a more efficient transfer of force from the lower body to the weight being lifted. Ankle Mobility: Allowing the Knees to Flex into the SquatAnkle mobility is crucial in the squat as it allows for proper depth and alignment. Sufficient ankle dorsiflexion enables the knees to travel forward over the toes, facilitating a more upright torso position and optimal distribution of weight. Limited ankle mobility can lead to compensations such as excessive forward lean or lifting the heels, increasing the risk of injury to the knees, lower back, and ankles. Improved ankle mobility enhances squat performance, reduces strain on joints, and promotes better movement mechanics. Compound Movement: Practicing the Entire MotionUsing assistance, such as a resistance band or a support structure, can help practice a squat movement by providing stability and support. Assistance allows beginners or individuals with limited mobility to gradually acclimate to the proper movement pattern without fear of falling or losing balance. It also helps to reinforce correct alignment and technique, allowing for a safer and more controlled descent and ascent during the squat. Over time, as strength and confidence improve, assistance can be gradually reduced until the individual can perform the squat movement independently and with proper form. Squat Closing ThoughtsThe squat movement is a fundamental exercise that engages multiple muscle groups and joints, making it a cornerstone of strength training and functional fitness. While there may not be a one-size-fits-all definition of perfect form due to individual differences in anatomy and mobility, adhering to general principles is paramount. These principles include maintaining a neutral spine, engaging the core and glutes, tracking the knees over the toes, and achieving sufficient depth while maintaining proper alignment. Following these principles helps distribute the load evenly across the body, minimizes the risk of injury, and maximizes the benefits of the exercise. Whether performing bodyweight squats, front squats, or back squats, focusing on these principles ensures a solid foundation for building strength, stability, and mobility in the squat movement.

Each year I write down the most important things I read, see, hear, and think about. These notes help me reflect on what I am learning and how I am growing both personally and professionally. Here are several of my 2023 thoughts. I hope it inspires you to keep your own list!

**The notes above are a combination of my own thoughts, adaptations of other people's thoughts, and likely even a few direct quotes from others. I'm grateful for the many brilliant people teaching me along the way!**

Most of my clients come to the clinic because a certain movement or activity is causing them pain. For example, it hurts when they go down stairs or it hurts when they are bending forward to brush their teeth. A certain way of moving and a certain pattern of muscle activation is setting off the alarm signals. In these moments, we need to unload and unwind the nervous system. Keep moving, but without triggering the pain response. The way to accomplish this is to gradually move into and around painful ranges of motion. Controlled movement around the pain slowly desensitizes the painful movements and teaches the brain that movement is safe. This whole experience is a learning process. Many movement patterns become so habitual that they go unnoticed. We don’t think about how our knees bend when walking down the stairs or how the spine bends when we brush our teeth. Movement becomes automatic and subconscious. When pain occurs, movement all of a sudden becomes very conscious. Painful movements are sensitive movements, and the body develops new patterns to minimize pain. The process of identifying pain and retraining it can be complex. At times, the learning process can feel like pushing a large rock up a mountain. The more chronic the pain, the longer that rock has settled into the earth. Just as the rock doesn't want to budge, our old habits can be hard to change. To help someone out of pain, we need to identify the specific pattern causing someone’s pain and retrain a new pattern. We need to unlearn certain movement habits and engrain a new muscle memory. This entails calming things down and gradually building them back up. In this post, I am going to share several of the movement principles I incorporate with my clients to help them calm down symptoms and gradually learn new movement habits to get out of pain (and prevent injury in the future). Principle 1: Slow before FastMovement gives our brain tons of input about location of our joints, amount of pressure, speed of movement, and more. This input is important for body awareness and preventing injury. If the input comes in too quickly, the body has to react to the movement and no learning occurs. One of the ways to slow down the input to the brain is to slow down the pace of movement. A slower pace helps someone feel when and where a movement starts hurting. Controlling the speed of movement helps control the speed of learning. In the clinic, I’ll use a TRX or some other form of assistance to help slow down a movement to make the learning curve easier. Principle 2: Single and Simple before Compound and ComplexBreaking down a compound movement into smaller parts is a highly effective strategy for retraining movement. The process of disassembling then reassembling allows us to separate the parts from the whole movement. During this process, you can identify a weakness or inflexibility that is driving the problem. For example, if someone has pain going down the stairs, we can isolate the major joints performing the motion. Instead of multiple joints receiving input, we can train each joint how to move without triggering pain. Joint by joint we rebuilt the entire sequence. Principle 3: Stable before Unstable SurfacesThe sensors within muscles, tendons, and ligaments are constantly providing the brain with feedback about position, pressure, pain, temperature and more. This barometer is important for how our muscles adapt and react to the outside world. Starting with a stable surface allows these receptors to find a set point. In the clinic, I’ll start on a solid, firm ground before training on unstable surfaces. I make sure the client can find their balance and center of gravity on the ground before adding a more complex variable. Principle 4: Partial Range of Motion before Full Range of MotionAs our movements get bigger and our tissues stretch further, we put strain on the input sensors that I’ve mentioned above. When these sensors are repetitively strained at their end-ranges, their ability to provide reliable information becomes hypersensitive. When getting out of pain, we need to start in a range of motion that doesn’t aggravate these joint sensors. Beginning in a neutral position where our muscles are strongest is typically the best way to calm down symptoms. In the clinic, I'll start people in an open joint position where there is the least strain on the joints and soft tissue. As their pain subsides and tolerance increases, we gradually start challenging their nervous system through full ranges of motion. ConclusionUsing these principles (among others) allows clients to understand which movements, postures, and environments are causing their pain. By starting slow, small, and simple the learning process can occur with less distraction. This allows us to calm down symptoms while keeping the patient in control of their symptoms as they gradually retrain their nervous system!

We need to have very strong primary movement patterns,

|

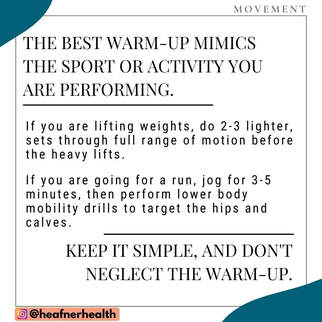

| It is well-established that the best way to warm-up is to perform the same motions required during the training session, but at a lesser intensity. This allows the nervous system, endocrine system, and other vital organ systems to initiate all the proper mechanisms without getting injured. For example, during a warm-up the sympathetic nervous system turns on, blood vessels dilate to bring oxygen to the body, and specific hormones are released to prepare the body for more vigorous activity. The backslap and a few other full range of motion dynamic stretches accomplish all the necessary components to prepare the body for maximal effort! |

Listen to Your Body

Many factors play into a successful warm-up, but the most important is listening to how your body feels.

- If you feel sore during a warm-up, you likely need a few extra minutes to help ramp up your system for exercise.

- If specific movements feel restricted, spend extra time opening up those movements so your range of motion and strength is available.

- Lastly, try to enjoy the warm-up! Most people do not leave enough time to warm-up; and therefore, it becomes burdensome. If you consciously make time and enjoy the warm-up, your mind and body will be much more prepared for the task at hand!

-Jim Heafner PT, DPT, OCS

Owner, Heafner Health Physical Therapy

Owner, Heafner Health Physical Therapy

Learn how to determine when it’s safe to continue a workout and when to stop exercising if pain arises.

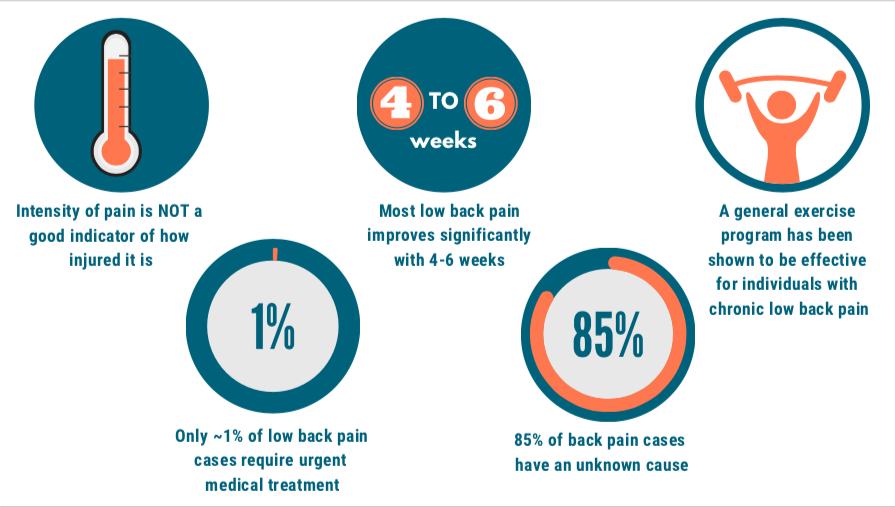

Until recently pain has been thought to be an indicator of the amount of tissue injury present in the body. The belief is that a high amount of pain equates to a serious injury, and a small amount of pain equates to a minor injury. However, through extensive research, we now know that pain has surprisingly little correlation to the amount of tissue damage present. For example, it’s estimated that 40% of people without any low back pain have at least one “bulging” disc on a lumbar spine MRI. Instead of pain acting as a barometer for tissue damage, it should rather be thought of as an alarm system, warning you about actual or potential threats to continuing a workout.

When is it Safe to Continue Exercising?

Since pain does not equate to tissue damage, does that mean you can exercise past the point of pain without any consequences? No pain, no gain…right? Not quite! As mentioned above, pain is an alarm system meant to alert you to potential danger. In the case of exercising, the danger may be caused by a specific movement or a specific weight machine. However, just as alarms can misfire, your internal protective mechanism can do the same. Factors such as fear, stress, anxiety, lack of sleep, overactivity, poor nutrition, and many others can influence your alarm system’s perception of danger. When exercising, do not underestimate the importance of these factors.

In my clinical practice, I always tell patients, “respect the pain and evaluate the symptoms you are feeling!” If the pain persists, stop exercising. If the pain decreases by modifying the exercise, warming-up the muscle, or simply desensitizing the movement with a few repetitions, it’s likely okay to continue exercising!

In my clinical practice, I always tell patients, “respect the pain and evaluate the symptoms you are feeling!” If the pain persists, stop exercising. If the pain decreases by modifying the exercise, warming-up the muscle, or simply desensitizing the movement with a few repetitions, it’s likely okay to continue exercising!

Sharp Pains

Sharp pains may indicate that a muscle, ligament, or joint is actively getting injured or overstressed. These pains quickly catch our attention because they travel along fast-moving nerve cells to warn us something is not in balance.

Nerve-related Numbness or Tingling

Numbness, tingling, or sudden muscle weakness may indicate that a nerve is getting angry because the normal amount of oxygen around the nerve has been altered. In my book, Making Sense of Pain, I discuss how the nervous system is highly sensitive to changes in oxygen levels. The nervous system weighs only two percent of our total body weight yet requires 20 percent of our total oxygen supply. When a nerve becomes tensioned or compressed, its oxygen flow is altered, often resulting in perceived numbness, tingling, burning or aching.

Increased Pain

Finally, pain that continually increases is a good reason to stop a workout. Increasing pain may indicate that the aggravated tissue is repeatedly getting over-stressed. This can lead to an overuse injury, which could require you to stop exercising for several weeks.

Sharp pains may indicate that a muscle, ligament, or joint is actively getting injured or overstressed. These pains quickly catch our attention because they travel along fast-moving nerve cells to warn us something is not in balance.

Nerve-related Numbness or Tingling

Numbness, tingling, or sudden muscle weakness may indicate that a nerve is getting angry because the normal amount of oxygen around the nerve has been altered. In my book, Making Sense of Pain, I discuss how the nervous system is highly sensitive to changes in oxygen levels. The nervous system weighs only two percent of our total body weight yet requires 20 percent of our total oxygen supply. When a nerve becomes tensioned or compressed, its oxygen flow is altered, often resulting in perceived numbness, tingling, burning or aching.

Increased Pain

Finally, pain that continually increases is a good reason to stop a workout. Increasing pain may indicate that the aggravated tissue is repeatedly getting over-stressed. This can lead to an overuse injury, which could require you to stop exercising for several weeks.

Key Takeaways

- Pain is like an alarm system designed to keep you out of danger.

- Numerous factors such as nutrition, sleep, stress, and fear turn up or turn down the sensitivity of your internal alarm system.

- If you experience pain during a workout, stop and evaluate the symptoms to determine if further exercise is safe.

- If the pain decreases by modifying the exercise or further warm-up, it’s likely okay to continue exercising!

- Sharp pain, nerve-related numbness or tingling, and/or increasing pain are all reasons to temporarily stop exercising.

Written by: Dr. Jim Heafner PT, DPT, OCS

Originally written for the IDEA fitness blog with contributions from OPTP.

Originally written for the IDEA fitness blog with contributions from OPTP.

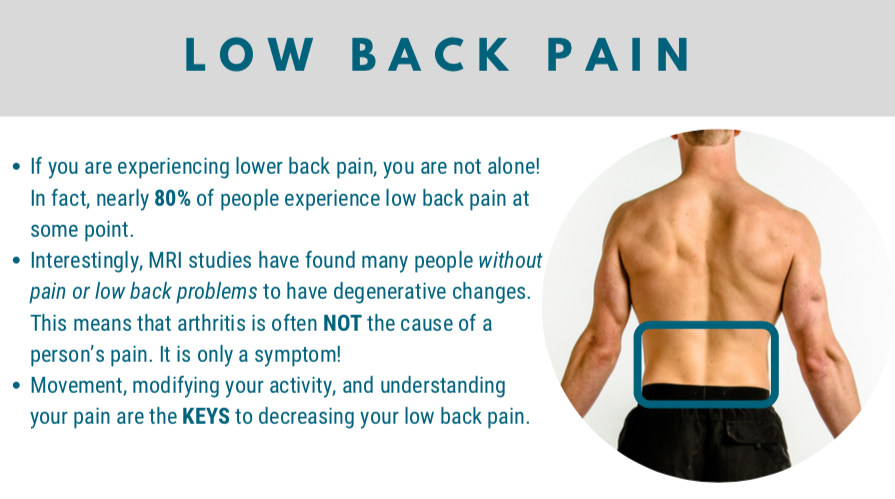

If you have ever experienced lower back pain, there is a good chance you can recall some very specific details about the experience. For example, you may remember where you were, what you were doing, and how intense the pain was for 24-48 hours after the injury. People often remember this experience (and those similar to it) because the human brain prioritizes experiences that require a significant amount of attention. On the same list of significant experiences (even though the emotional response is different) would be watching the birth of your child, seeing a beautiful sunset, getting married, etc... Any experience that overwhelms the senses (sound, sound, touch, smell) is likely to be remembered because of the intense emotional association.

If you are currently experiencing low back pain or worry about having low back in the future, this article will help you better understand pain and quickly manage any symptoms that may arise.

If you are currently experiencing low back pain or worry about having low back in the future, this article will help you better understand pain and quickly manage any symptoms that may arise.

Understand Your Pain

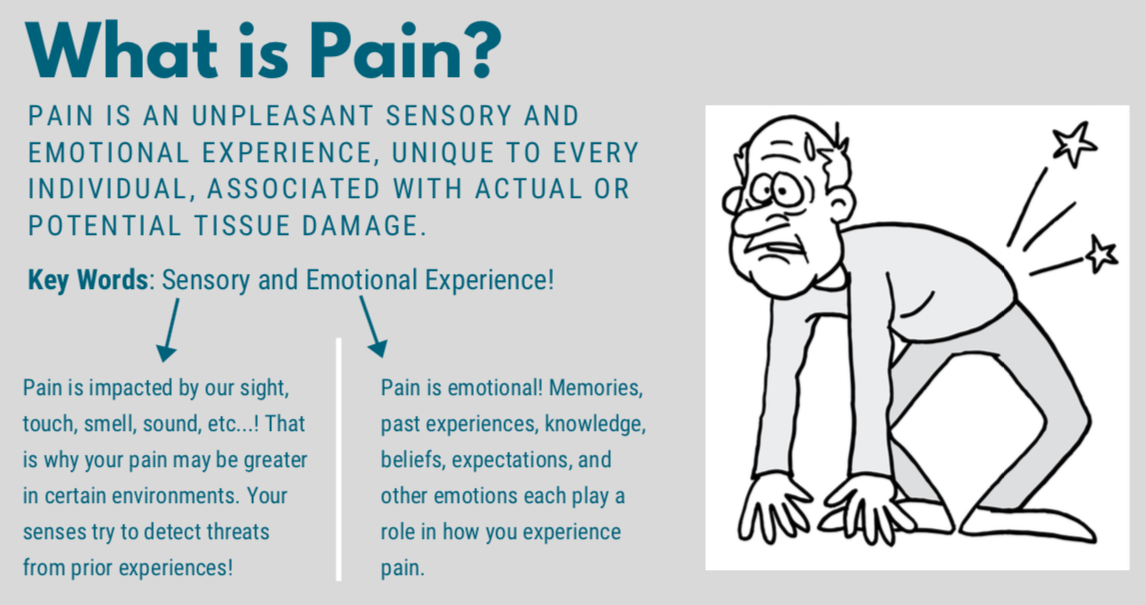

At this point, you may be thinking, "Leave the emotions out of it...I strained my back muscle, not my brain!" While the low back muscle may be the injured tissue, it is necessary to look beyond the muscle to fully understand why the magnitude of your pain. Pain, by definition, is an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience, unique to every individual, associated with actual or potential tissue damage. Therefore, it is impossible to seperate the pain from the emotional response.

Regarding low back pain, it is important to know that pain is rarely caused by a serious medical issue (such as a fracture or cancer), that would require urgent medical attention. The majority of lower back pain (>70%) is due to tissue sprains and muscle strains, which respond well to rest, easy exercise, and education. For this reason, X-rays and MRIs are not indicated as they often do not correlate with pain.

Regarding low back pain, it is important to know that pain is rarely caused by a serious medical issue (such as a fracture or cancer), that would require urgent medical attention. The majority of lower back pain (>70%) is due to tissue sprains and muscle strains, which respond well to rest, easy exercise, and education. For this reason, X-rays and MRIs are not indicated as they often do not correlate with pain.

Learn the Back Facts

- Most people recover from a low back injury in 4-6 weeks (50% recover in ~2 weeks, 80% recover in ~6 weeks).

- Intense pains should resolve within a few days. Moderate to mild symptoms may persist for a few weeks.

- The severity of the injury, level of stress, fear of movement, and other factors will all impact recovery time.

- The use of ice or heat has not been determined by the research. I often recommend ice for the first 24-48 hours, then heat after 48 hours. However, individual preference is most important. Ultimately, do what feels good!

- NSAIDS and over the counter medications can be helpful, but should not be taken without physician consent.

- Bed rest should be limited after a back injury. Gentle exercise and movement is indicated as soon as possible!

Get Moving (Gradually and Easy): The Goldilocks Principle

The story of Goldilocks is about finding the right fit, and I can tell you that little blonde girl was onto something! The idea of not too much, not too little, but just the right amount applies to many facets of life. Gradually increasing activity to improve pain and gain strength is certainly no exception. The human body gets stronger and more resilient through a process of gradual, progressive exposure and strengthening. To get stronger, you slowly and steadily lift heavier weights over time. If you lift too much too soon, you’ll become sore, or worse, injured. However, if you don’t lift enough weight to challenge your body, you’ll never get any stronger. The exact equation of not too much, not too little, but just the right amount is unique to everyone and will change over time as your body matures.

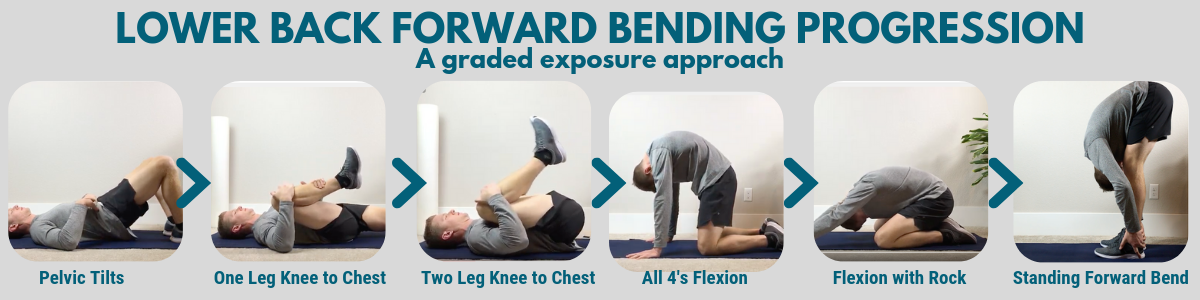

As you are recovering from a lower back injury, start moving slowly in small ranges of motion. As your fear decreases and ability to move increases, gradually increase the range of motion and demands of the movement. For example, in the progression below, I show how to gradually improve bending forward.

As you are recovering from a lower back injury, start moving slowly in small ranges of motion. As your fear decreases and ability to move increases, gradually increase the range of motion and demands of the movement. For example, in the progression below, I show how to gradually improve bending forward.

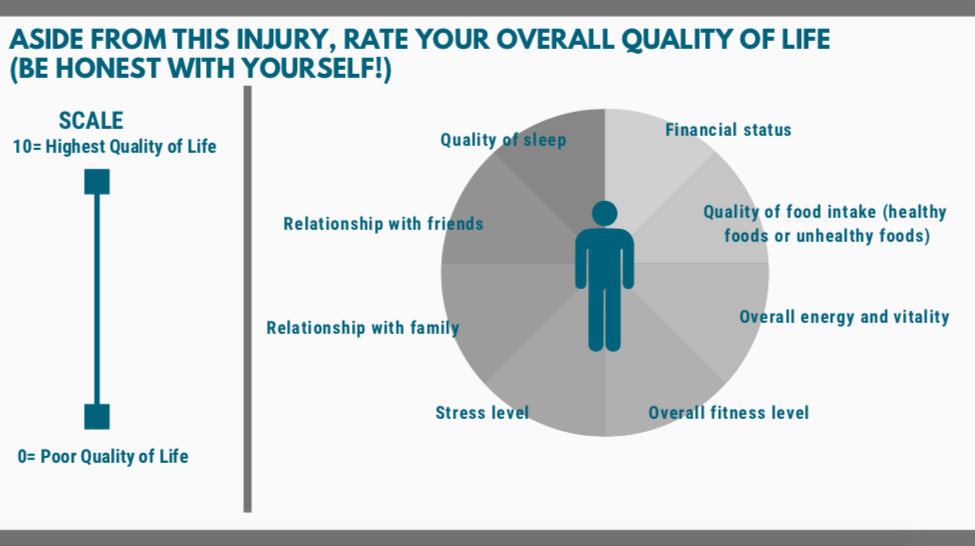

Don't Neglect Other Areas of Your Health

If you are experiencing pain, it is easy to blame the pain solely on a physical or structural problem. With that being said, I am not discrediting the tissue injury that may have occurred. After a traumatic event, such as a car accident or lifting injury, inflammation and other chemical signals (redness, warmth, swelling) can be observed. However, since you just learned about the complex nature of pain, I urge you to think about other areas in your life that may impact your pain response. In these moments, I always tell my patients to 'respect the healing process.' This includes focusing on good sleep and rest, reducing or minimizing stress, eating a well balanced diet, and performing gentle movement (as discussed above). In the picture below, I outline many of the areas that impact your experience of pain.

Remain Positive and Optimistic

Finally, mindset is key! Following an injury, our brains naturally revert to the worst case scenario. Fear, anxiety, worry, and other negative emotions flood your mind. While listening to these emotions is important in the moments of actual threat, the majority of these fears are not accurate. The reality is that you will most likely return to your normal life in a matter of days or weeks. In the midst of pain, having a mantra, such as "my back is strong and health," can help slow down the negative emotional response. By mindful repeating or thinking optimistic thoughts, you will strengthen the brain connections geared toward optimism and happiness.

Jim Heafner PT, DPT, OCS

Heafner Health Physical Therapy

Boulder, CO

Heafner Health Physical Therapy

Boulder, CO

If you are looking for low back self treatment strategies, click here!

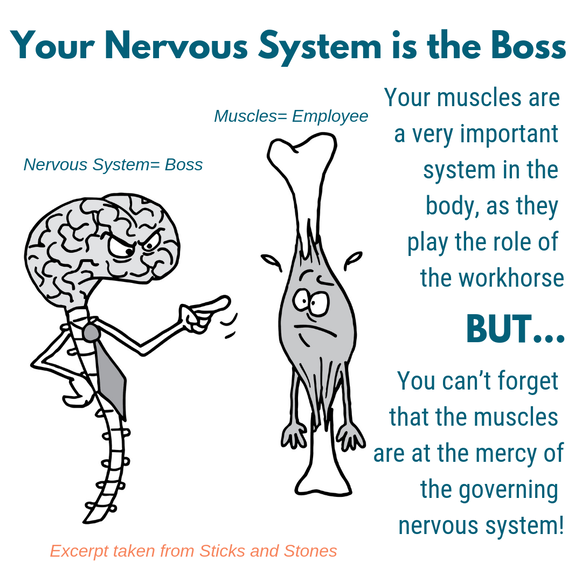

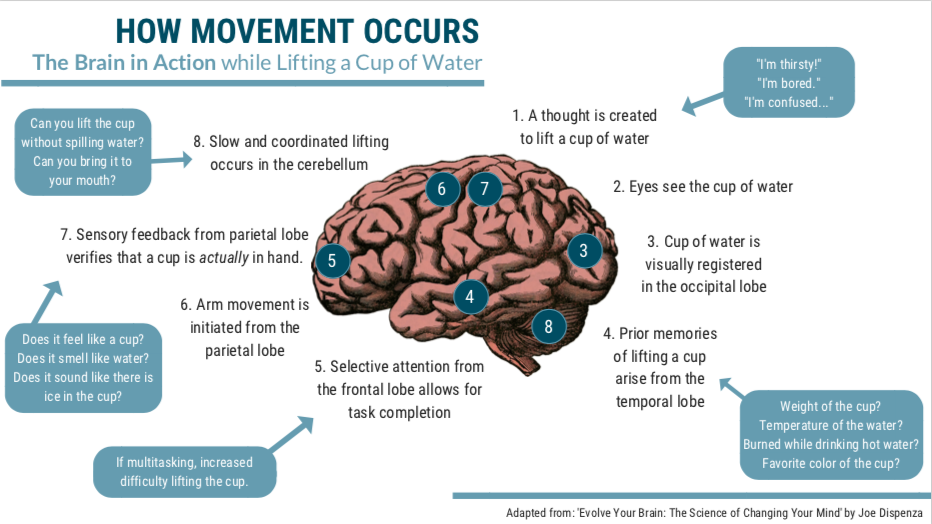

Your muscles are a very important organ system in the body, as they play the role of the workhorse in every movement you make. However, you can’t forget that the muscles are at the mercy of the governing nervous system. Everything you feel is actually an experience created by your brain and nervous system. For this reason, muscle memory is somewhat of a misnomer! Muscle memory is a term used to describe how our nervous system and brain work together to build strong connections and develop movement habits for specific activities. For example, if someone repeatedly practices throwing darts at a target, they will most likely improve their accuracy over time. While the fingers and forearms feel the movement, the 'memory' is really encoded in the brain. At the same time, if someone postures their muscle is a certain position for working for multiple hours each day, the movement or posture will remember this position.

The nervous system tells the muscles how to act and what to feel. If there’s tightness, stiffness, guarding or pain in a muscle, it’s often because the boss is unhappy and the employees are just carrying out the boss’ orders. For example, think of the last time you exercised when you were tired, stressed or hungry - it probably wasn’t a great workout. If the boss (your brain and nervous system) is in a bad mood, the employees (your body) feel the strain. Allowing the boss to calm down or letting the boss rest can reduce stress on the employees. In response, the boss can stop the overbearing micromanagement, which is causing the employees to revolt.

Following an Injury, Your Muscle Memory is Altered!

While you do not remember this learning process, it occurs through countless hours of practice and repetition. As a new father, I see these repetitions happening in my baby daughter each day. While my daughter is not picking up a cup of water yet, she is starting to see objects, identify her hands, and reach for the objects. Over time, each piece of the puzzle will come together and her 'muscle memory' will be encoded.

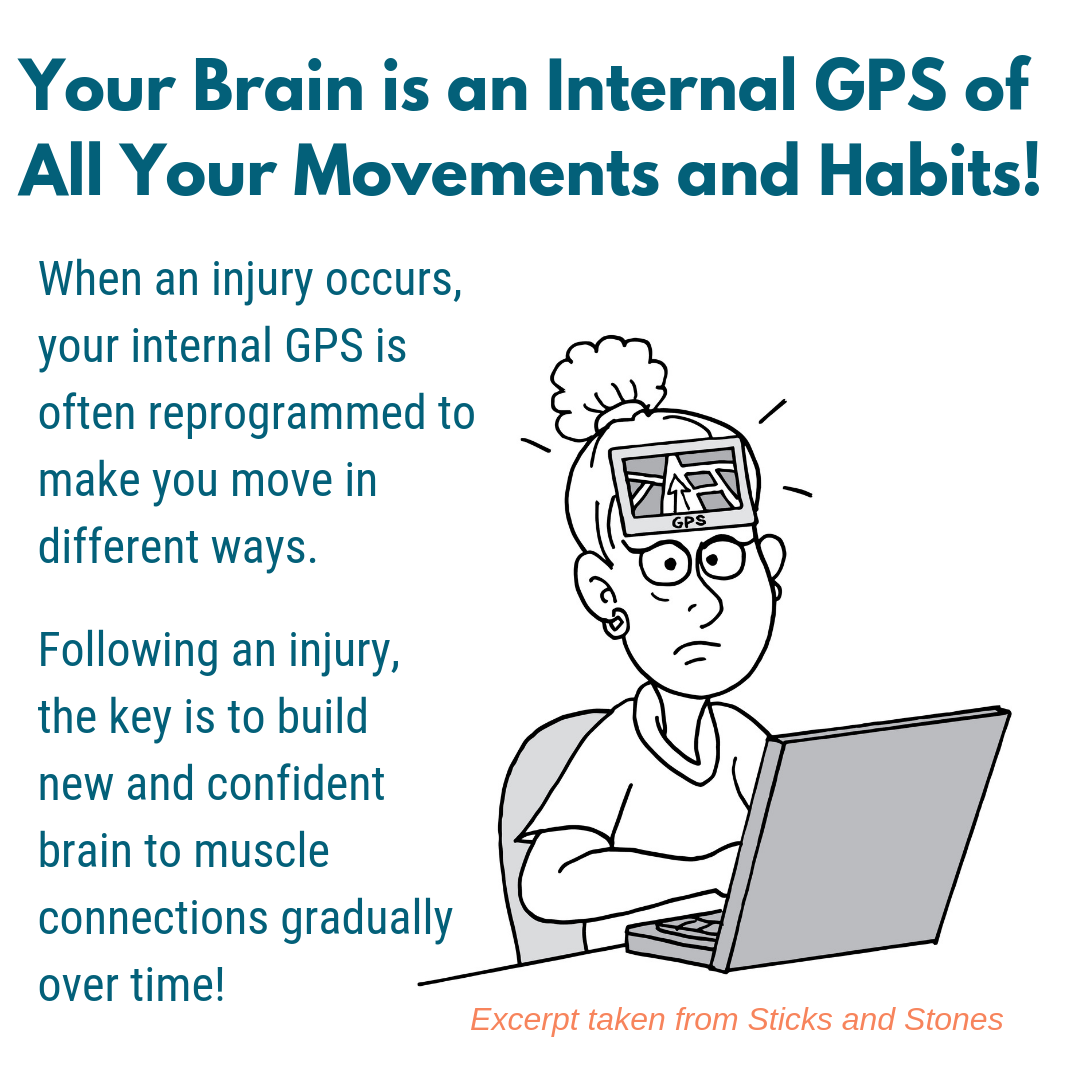

In your own body, think of this “muscle memory” as an internal GPS that’s aware of every movement you make. When an injury occurs, your internal GPS is often reprogrammed to make you move in different ways. With an injury, there can be different messages sent between the brain and the muscle, meaning your “muscle memory” has been disrupted. After some time, your internal GPS may no longer be able to accurately identify certain roads on your body’s map. While the injury is healing, the brain and body often coordinate alternative, compensatory strategies for certain movements like a limp, awkward bending mechanics, stiff movements, or limited range of motion. These protective phenomena are much like how a GPS detours to an alternative route because of a road closure.

The movement detours may feel uncomfortable or less efficient, much like driving down a heavily trafficked and overcrowded street. This is because your brain isn’t familiar with the detour, which may place new or different stresses on the system. By building new and confident movement strategies, you can experience minimal issues while the main road is being repaired. However, once the body’s healed and the route’s obstructions are cleared, it’s important to return to the main road without fear.

Keys Points and Takeaways

- Muscle memory is a term used to describe how our nervous system and brain work together to build strong connections and develop movement habits for specific activities.

- When an injury occurs, your internal GPS is reprogrammed to make you move in different ways.

- Mindful movement practice strengthens the 'muscle memory' after an injury.

Learn more of these analogies from the Sticks and Stones book by Jim Heafner and Jarod Hall.save $10.00 with promo: wordsmatter |

Heafner Health

Physical Therapy

Manual Therapy

Movement Specialists

Pain Management

Archives

April 2024

February 2024

January 2024

June 2023

April 2022

October 2019

February 2019

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

January 2017

September 2016

August 2016

July 2016

June 2016

May 2016

April 2016

March 2016

February 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed